SEOUL — A diary written by a Korean man working at wartime brothels in Burma (current Myanmar) and Singapore during World War II has recently been found, a discovery that could shed light on the truth behind the role of the Imperial Japanese Army in controversial comfort stations for Japanese soldiers.

The Korean man took part in the “4th comfort corps” that left Busan Port on the Korean Peninsula in 1942. He returned home in late 1944. His diary is the first of its kind found in Japan, South Korea and elsewhere. On the issue of so-called “comfort women” for the Imperial Japanese Army during the war, many of the testimonies were made several decades after the end of the war. The diary written by the Korean man — a third person who had actually witnessed wartime brothels — is important material to pave the way for cool-headed discussions on the thorny issue.

The diary was discovered by Ahn Byong Jik, professor emeritus at Seoul University, who specializes in modern Korean economic history and is knowledgeable about the comfort women issue. A museum in the suburbs of Seoul found a diary and other materials at a second-hand bookshop about 10 years ago. Ahn found the diary while combing through the materials. Kyoto University professor Kazuo Hori and Kobe University professor Kan Kimura are currently translating the diary into Japanese.

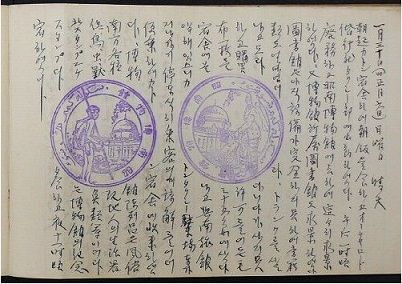

The diary was written by the man from Kyongsang-namdo on the western part of the Korean Peninsula while working at the wartime brothels from 1943 to 1944. It was written in Chinese characters, katakana and Korean alphabets.

The man was born in 1905 and died in 1979. His diary written from 1922 to 1957 can be seen today. Nevertheless, the part of his diary which covered eight years during which the man could have been engaged in recruiting comfort women has not been found.

In the diary, the man wrote on July 10, 1943, “At this time last year, I boarded a ship at Busan Wharf and took a first step on the southbound trip.” On April 6, 1944, he wrote, “When a comfort squad left Busan two years ago, Mr. Tsumura who came as the head of the fourth comfort corps was working (in a market).”

A research report compiled in November 1945 by U.S. soldiers who questioned managers of comfort stations caught in Burma says that 703 comfort women and about 90 business operators left Busan Port on July 10, 1942. The accuracy of his diary is backed up by the fact that the date of their departure is the same.

Ahn says, “It is certain that the records compiled by the U.S. military refer to the fourth comfort corps. The existence of comfort corps suggests that comfort women were conscripted as part of systematic wartime mobilization.” As opposed to the view generally held in South Korea that comfort women were forcibly conscripted by Japanese military and police, Ahn says, “Comfort women were recruited by business operators in Korea, and there was no need for the military to abduct them.”

In the diary, the man touched on relationships between comfort stations, comfort women and the military. He wrote on July 19, 1943, “Two comfort stations that belong to a flying corps were handed over to the logistics command.” On July 29, 1943, he wrote, “I’ve heard that Haruyo and Hiroko who had left (a comfort station) to have conjugal relations (with their husbands) returned to Kinseikan as comfort women again.”

The Korean man also wrote in his diary on Aug. 13, 1943, “Comfort women went to see a movie, saying that the railway corps will run a movie.” He wrote on Oct. 27, 1944, “I was asked by a comfort woman to remit 600 yen, so I withdrew her deposit and sent it from a central post office.”

The issue of so-called “comfort women” became a major social issue after a group of South Korean women demanded the governments of Japan and South Korea shed light on the truth, apologize and compensate them in 1990. The Japanese government acknowledged in August 1993 that the then Imperial Japanese Army had been involved either directly or indirectly in setting up comfort stations and transporting comfort women.

In his statement issued at that time, then Chief Cabinet Secretary Yohei Kono offered an apology on behalf of the government, saying, “Undeniably, this was an act, with the involvement of the military authorities of the day, that severely injured the honor and dignity of many women.”

But in 2007, the first Cabinet of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe endorsed its written reply to the Diet which read, “There are no descriptions seen in the materials discovered by the government that directly show so-called abductions by the military or by the authorities.”

日本人なら見ておいて欲しい動画 はコメントを受け付けていません

日本人なら見ておいて欲しい動画 はコメントを受け付けていません

エントリ (RSS)

エントリ (RSS)